So, to do a scene in the style Rom-Com is to dictate, to a certain degree, what happens. That on top of the problem with doing a scene in the genre of comedy, which is effectively to say "do a scene, but it MUST be funny." Pressure!

So I've been thinking a bit about the Rom-Com lately and even coming up with a structure (or rather a path) to improvising a full one. I'll let you know later what comes out of it, but it's nearly there. But, it seems if you understand a few basic rules about what makes a Rom-Com, and what it is people enjoy about them, you should be able to steer your way through one.

Of course, the Rom-Com journey can very easily be seen as a classic Hero's Journey, in which the thing the hero is searching for (knowingly or not) is Love and he or she has to give up a lot or face great strife to get it. But in doing so he or she becomes a better person and makes the world a better place. They are often very much like quest movies because Love is so often treated in them like a mystical, magical force. A force which the hero often fights against but is ultimately swept along by. A force which guides his or her destiny.

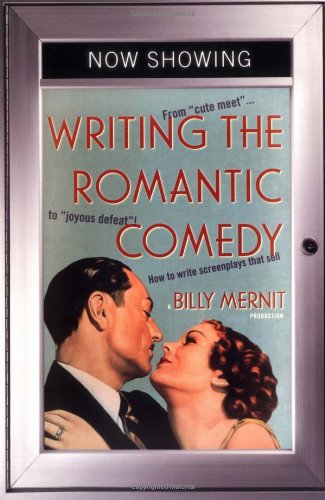

A couple of things have helped me understand this genre a lot more: one is watching a few of them; the second is the excellent book Writing The Romantic Comedy by Billy Mernit.

Book available here: Writing the Romantic Comedy (Amazon.com)

Billy Mernit also has a blog and recently he listed 5 Rom-Com Truisms. They apply more to writing, but they are interesting to note, and some are directly applicable.

- "The primary challenge lies not in creating obstacles to keep the couple apart, but in convincing the audience that these two people truly do belong together."

- We should understand the protagonist's emotional logic. Especially when it comes to reluctance in / resistance to getting together.

- What the protagonists lose by being together must be important: the stakes must be high.

- #4 doesn't normally apply directly to improv (it's about writing good roles for women), because we are our own writers, and in general women play women. But it does apply when men play women and also vice versa, because there is a tendency here to make the characters stereotypes or 2-dimentional.

- "The most effective function of a subplot is to show how the protagonist is transformed by love."

If I was to recast these for improv, I would state them as follows:

- We (the audience) must want the characters to get together.

- We must understand why they are not getting together.

- One or more of the protagonists must have something important they must give up to get together.

- Make the characters interesting not just people obsessed with other people or there simply to fall in love.

- As well as all that love stuff, show the protagonists growing and becoming better people, being transformed by the process.

See also: the Genre Guru Genre Guide to RomCom.